“People say nothing is impossible, but I do nothing every day.”

— Winnie-the-Pooh

Your brain can’t solve complex problems and focus on tasks at the same time. So “doing nothing” isn’t lazy. Doing nothing is essential.

If, like me, you are wondering where January went, whilst concurrently bracing yourself for the impending onslaught of half-term holidays, this article is for you.

I’m going to share a brief, neuroscience-backed tip to help you to pause for five minutes - not only now whilst reading, but in the future, when you need a nudge.

So take five. Put your phone into flight mode, get yourself a coffee, glass of wine or an Aperol Spritz if you must, and find somewhere peaceful to sit and enjoy a short read.

Right. Bad news first.

You need to engage two areas of the brain for complex problem solving. And yet, these two areas CANNOT operate simultaneously. Therefore, you need to create the right conditions to help things along and give yourself the best chance. For ideas on how to best to this, keep reading or download this month’s worksheet.

And now for the good bit (especially if you are a fan of Piglet or Pooh).

Your brain’s salience network monitors what’s going on - externally and internally - to detect what's most important at any given moment. When it finds something that requires focused attention, like a task, a threat or a problem, the Executive Control Network (ECN) is activated.

Think of your ECN as Piglet. Piglet is the lively friend you rely on to meet a deadline. You know who I mean. They’re always on it. Vigilant, completer-finishers who are generally armed with a to-do list. And most things on that list are visibly (and enviably) ticked off.

If however, your salience network finds nothing specific requiring attention, the Default Mode Network (DMN) is activated instead. The DMN is a very different beast. It is your creative, empathetic friend. The one who is reflective and taps into insight, gut feeling and sense of identity. They daydream and invent.

The DMN is, essentially, Winne-the-Pooh.

Yeah, yeah - but I’m an awesome multi-tasker, you say. Just show me the problem and I’ll get them both on it. But the very second you focus on a problem, your savvy little salience network starts scanning, and wakes up Piglet with a grunt. Pooh, meanwhile, sits dormant, neglected, barely even able to twiddle a furry thumb.

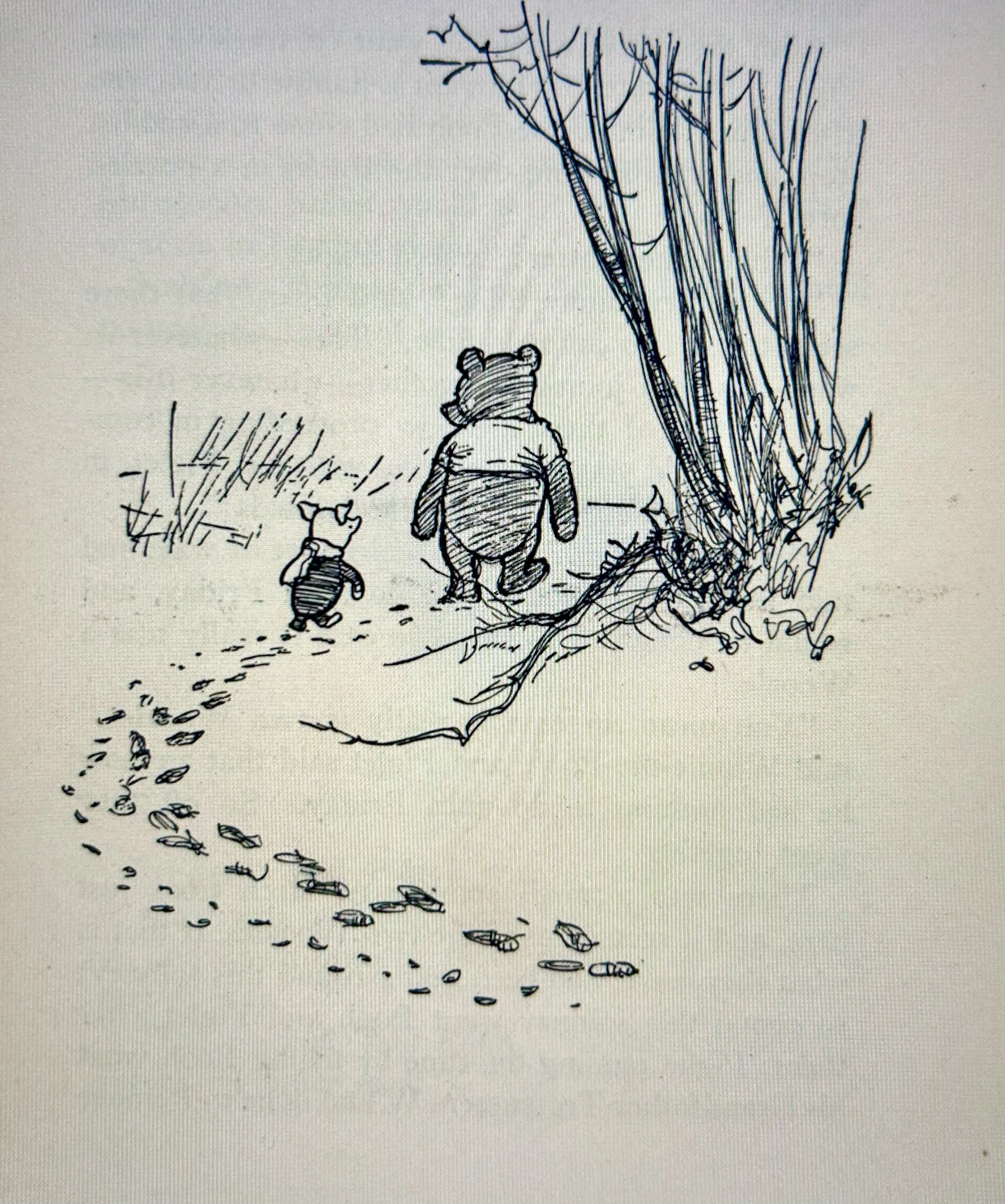

However good you may be at multi-tasking, the tragedy of these two companions is that they cannot function at the same time. The saving grace though, is that they complement each other and can work in rapid succession when you create the right conditions for them.

Pooh is not at his best when Piglet is agitated or anxious. Remember when Piglet gets so nervous about the dreaded Woozle footprints that he doesn’t realise that they are making the tracks themselves? Piglet’s myopic thinking adds to Pooh’s confusion, and it is only when Christopher Robin intervenes that either of them is able to see clearly again.

This is because, when you are focussed on a task, your brain cannot function effectively for complex problem solving. You simply cannot see the wood for the trees.

So when we’re doom-scrolling, rushing between meetings, or multi-tasking to be “efficient”, we’re hampering our best thinking. Because this intense focus on tasks means our ECN is activated and our DMN is closed down.

Pooh is described as a “bear of very little brain”. Like him, our DMN needs less cognitive load to really get going. Staring out of the window, going for a walk without a phone, letting thoughts drift without direction – these are all things which allow our DMN, our creativity, to flourish.

And there’s more good news…

When we first set up a problem, and then allow our mind the time and space to wander, our DMN and ECN begin to work in harmony. In this state, they can operate in quick succession, passing information from one to the other, and positively oscillating with the excitement of having some airtime. And it is in these conditions that we can access strategic thinking and complex problem solving.

This is exaclty why a solution that has been eluding us for some time, suddenly arrives unbidden whilst we’re staring into space, having a shower or walking the dog.

In Proust Was A Neuroscientist, Jonah Lehrer argues that artists like Stravinsky, Whitman and Proust anticipated neuroscientific findings before science confirmed them. The same can be said of A.A Milne; Pooh’s philosophy of doing nothing anticipates today’s neuroscience of the benefits of allowing the mind to wander. So apart from his somewhat alarming honey addiction, he really is a great role model.

The next time you’re feeling like you can’t take a break, or that you will be more efficient if you just push on through, take a leaf out of Pooh’s book:

Don’t underestimate the value of doing nothing, of just going along, listening to all the things you can’t hear, and not bothering.

Because he was, after all, smarter than he thought.